Hobo Feature article 1

This article by Rock Sociologist Simon Frith is from

Wedge, a radical magazine from the 1970's, which I bought in the Coventry Wedge Cafe / bookshop c 1977. Simon Frith was based at Warwick University as sociologist from 1972 into the 80's and so was familiar with the Coventry music scene.

HOW THE POP CHARTS WORK

By Simon Frith from Wedge Magazine Summer 1977

In this article, Simon Frith shows that the charts function in a peculiarly contradictory manner. They are used by companies partly to find out what people like. But they’re also used by the companies as a device for controlling the market – which must tend to work against their usefulness as a real indicator of public taste.

So by asking why the charts are important to the industry – rather than simply considering to what extent they’re rigged - we can perhaps get a clearer sense of the ways in which the commodity nature of mass music prevents it being of the people.

The charts have a good claim to be the most important institution in the record business. So many things depend on them – radio stations’ playlists, artists’. Performance fees, record company executives’ careers, retailers’ stocks, - that chart positions become fetishised, as the DJ’s read out the week’s list like it was a holy writ. It’s a strange sanctification for what is a routine exercise in market research.

For one of its commissions the British Market Research Bureau is employed by the British Phonograph Industry (the record companies’ trade organisation and a pressure group), the BBC, and the trade paper ‘Music Week’ to provide a continuing analysis of the record market in Britain. The singles and LP charts are only part of the service provided by BARS (British Analysis of Record Sales) to its subscribers and there purpose is quite simply, to give an accurate summary picture of the previous week’s sales figures.

The most accurate way of drawing such a picture would be to collect the sales details from every record retailer in the country. This is impossible, as a matter of both time and expense, BMRB has to record the sales from a sample of shops. There are two problems involved – the sample must be representative and the returns from the shops involved must be accurate – and the solutions to these problems are not always compatible. If, for example, BMRB follows the BPI’s suggestion that their sample be increased from 300 to 600 retailers, of which only a half would be used each week (for security reasons to which I will return) then it is likely that the retailers themselves, never sure whether their sales diaries would be used or not, would become less conscientious in their returns. As it is BMRB are well pleased with the cooperation of their sample – 75% of the diaries are returned each week, and the inevitable mistakes made by assistants copying down record numbers are not common enough to be statistically significant. BMRB is confident enough of the sales figures it feeds into its computer; the problem is meaning and this depends on the sample involved.

Sampling is the basis of all market research and there are no particular problems involved in the measurement of record sales. BMRB get sales accounts from record companies, shops are coded by their size and type of turn over, the sample is drawn up accordingly. The resultant formulas – converting the overall pattern of record sales into a list of 300 shops, converting the returns from these shops back into a national sales pattern – are complicated but not unusually so. Regional record sales don’t vary much, for example and when BMRB did, briefly, supply regional charts they proved unnecessary (the lack of regional variations is reflected in the similarities of local radio play lists.)> Account is taken of specialised outlets for such genres as reggae, and classical music is the only form which is genuinely under represented by the sample.

The only other obvious sampling defect is the continual refusal by Boots and W.H. Smith to provide sales returns. There is little other evidence tht BRMB’s retail sample is unrepresentative and a comparison of its weekly sales estimates with companies’ final sales figures at the end of each year reveals a reasonably good match.

The Industry’s Response.

From its own point of view BMRB is engaged ina routine form of market research and achieving more than accurate results. The importance of each chart lies not in its activities but in the music industry’s response to them. In the record business this measure of the previous week’s sales can – through its effect on radio plays, on record company promotion, on retailers’ stocks – determine future sales. Hence the bizarre situation that in an industry paying a considerable amount of money for an accurate measure of record sales there are people deliberately trying to make this measure inaccurate.

For BMRB chart ‘fixing’ is not a problem of morality but of accuracy. They don’t care who buys the records, their concern is that the sales pattern revealed by their sample can be translated into a national description. If a record company decided to buy 300 copies of its latest disc in every shop in the country that’d be fine by BMRB and into the charts the record would go; the problems only arise when such buying is happening only in the sample shops, such that the results do not reflect national sales. To give a concrete example: some record companies distribute money-off record tokens in discos. This has an immediate impact on sales, as the kids rush to the shops to get their 30p singles, and these are ‘genuine’ sales, BMRB measures; its only rule is that such tokens aren’t specific to chart shops, in which case the sales, while still ’genuine’ would no longer represent a wider buying pattern.

It is not difficult for record company reps to put together a list of chart return shops and while BMRB is confident that it spots the clumsier hypes through its phone checks and security rules, it is difficult to see how it could counter a really systematic effect to utilise its ‘active’ list (hence BPI’s suggestion that the sample be doubled and used more selectively), but, on the other hand, it is equally difficult to see the long term benefits of such hypes – their effect is to undermine the industry’s trust in the charts. Such fixing may be an extremely profitable way to break a particular record, but success is not guaranteed and failure has ramifications throughout the business. If experience were to suggest that the charts were not a good guide to what to stock and play and promote, to what the public did want, then the charts would loose their function.

There is already some distrust of the bottom part of the Top 50 – many shops and playlists emphasis the Top 30 – the fact is that these 30, in both the singles and albums charts, account for about 80% of record sales. The difference recorded between the records in the lower part of the BMRB chart sample are often statistically insignificant (and their precise chart position consequently meaningless). The only point in taking account of events down there is if they anticipate sales to come.

Avoiding Overproduction

The charts, more brutally than any mohair-suited mogul, show what happens when music is treated as a commodity – if a record is music’s commodity form, the charts are essential for the realisation of that record’s exchange-value. Most obviously, they are a sales device, part of the process by which consumer demand is created. A good part of the record business revolves around the attempt to make records time-bound, to persuade an audience to buy a record at the moment of its release, to get bored with it after a few weeks, to discard it for yet newer release, and so on. Records are released with a fanfare of publicity, advertising, plugging on the radio, articles in the press; they have a definite and active life during which time they can be heard on radio, on juke-boxes, in discotheques. The charts are the symbol of this activity; the temporary measure of a record’s current sales power, they become the permanent measure of its value.

But the charts are more than a form of publicity and promotion, a part of the process goes through which demand is controlled and manipulated. They are also important inasfar as musical demand can’t be completely controlled and manipulated. Records are bought for their aesthetic use value and aesthetic tastes are difficult to predict and satisfy. Record companies have to make for more recordings than they are able to sell (the hit; release ratio is about 10% for both singles and albums) and to avoid overproduction they are dependant on a selection mechanism such that, having put their pieces of music on the market, they know which ones to mass produce, which ones to drop.

The charts provide by far the most accurate measure of consumer demand on which to base production plans, and if record companies issue a lot of titles, their profits are based on the big sales of a few of them. Because of the nature of recording costs, there’s a minimum number of sales which a record must reach to break even (an average of 15,000 for a single, 20,000 for an album – though the latter figure conceals huge variations). Beyond the break even point profits accumulate very rapidly and it pays companies far better, for example, to have one 100,000 seller and nine nil sellers than 10 10,000 sellers. The charts reflect this situation surprisingly accurately – if the discs in the Top 30 have passed their break even points and the discs from 30 to 50 reached them, most other records do not cover their costs.

There are obvious complications to this argument; records sell over time and over national boundaries, actual break even coasts can be reduced to a level at which profits are realised in sales that are not large enough to show in the charts. But the importance of such a selection mechanism for the industry is reflected in the fact that even specialist record producers, for whom a mass market is not the object, make use of charts of the sales of records within their genres.

It is the commodity form of the music that determines the use of the charts, not the musical form of the commodity, and, for this reason, most of the criticisms miss the point. The charts are usually attacked for lack of accuracy; the randomness of the lower placings is picked on and the suggestion made that the charts aren’t a real ‘measure’ of a record’s popularity; the argument is that the charts distort demand by granting to a few records the promotional attention denied to the majority. But the problem is not to investigate how, if at all, the charts distort market ‘demand’ the problem is to understand how the very notion of market demand shapes the meaning of music.

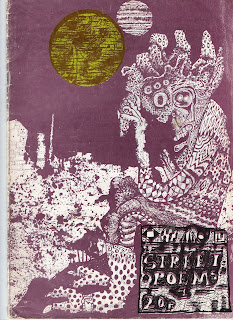

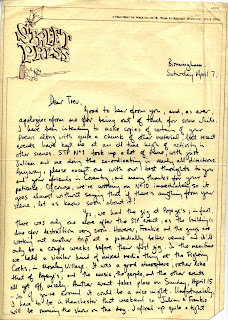

Roland and Sue were very supportive of our developing Coventry activities and I took copies of Streetpoems around the Coventry. With the demise of Broadgate Gnome in 1971 there was a need for another Coventry magazine that would act as a central focus and promote events and creativity. As I went around selling Streetpress and Streetpoems I knew we had to create one in Coventry even though money and resources weren't as easily available as in Birmingham. Also at that stage I'd never produced a magazine before and to learn new skills.

Roland and Sue were very supportive of our developing Coventry activities and I took copies of Streetpoems around the Coventry. With the demise of Broadgate Gnome in 1971 there was a need for another Coventry magazine that would act as a central focus and promote events and creativity. As I went around selling Streetpress and Streetpoems I knew we had to create one in Coventry even though money and resources weren't as easily available as in Birmingham. Also at that stage I'd never produced a magazine before and to learn new skills.